(Classic Racer Spring 1990)

Synonymous with Norton and later BMW, Vincent Davey's race team helped many British riders and even took along a few 'Pets' during one sponsorship deal. Peter Dobson traces their success story.

The Gus Kuhn Team made an instant impact on the motorcycle racing scene. Starting out mid-season of 1968, by the end of 1969 they'd won the British 500cc Championship, Castrol Championship, Duckhams Trophy, Grovewood Award and the Redex Trophy. On the strength of these achievements they marketed a range of sports and racing bikes and a host of 'bolt-on' goodies.

The late Mr. Kuhn was not involved though. Successful TT rider in the 1920s and later captain of the Stamford Bridge Speedway Team he had opened Gus Kuhn Motors back in 1932 and when he died in 1966 his son-in-law Vincent Davey became Managing Director.

'Dave' Davey, as he's known to family and friends, was born at Edlington, near Doncaster in 1926 and brought up in Barnet, Herts. He joined the army in 1945 and attended a military academy in Bangalore. Later he was commissioned in the 'Paras' and his love for bikes dates from his days as Transport Officer at Nazareth, Palestine.

When he returned to England Vincent joined Norton Motors and his association with Gus Kuhn came through his friendship with Frank Hullett, the advertising manager of 'Motor Cycle' who was also friendly with Gus Kuhn. When Mrs. Kuhn fell ill young Vincent was asked if he might like to run the motor cycle shop in London's Clapham Road.

In the '60s when the trade was on its 'uppers' Gus Kuhn Motors took on Rootes Group cars but Vincent decided to drop them and concentrate on selling Triumphs, BSAs and Nortons. By 1968 he made a further decision to concentrate exclusively on Norton's products. "And we were soon the biggest Norton dealers in the world," he says.

He tried racing in the early 1950s on a Rudge and a Manx Norton but the shop took all his time and he soon gave it up. His enthusiasm remained however, and on a visit to the Barcelona 24-Hour race with his friend Stan Shenton he decided to become a sponsor; partly out of interest in the sport and partly for publicity.

Mick Andrew rode a BSA at that event and Vincent asked him on the spot if he'd join the Gus Kuhn team. Mick turned out to be a brilliant choice and on his Norton debut at Lydden, the first time a Commando had been raced he finished second just behind Dave Croxford on a Seeley. "Old 'Crocket' was a bit surprised," says Vincent.

In 1969 Vincent bought two bikes from Colin Seeley; one with a G50 engine and the other with a 7R and Kuhn mechanics Frank Kately and Dave Sleat built another bike for Mick with a Commando engine in a Seeley frame.

Mick made his debut in the Isle of Man with fourth in the Production 750 TT race. Tom Dickie took fourth in the Junior on the Gus Kuhn Seeley 7R and third in the Senior on the Kuhn G50. Dickie also partnered Mick at Endurance races - something of a problem as Tom had one arm shorter than the other.

The team's first International success was Mick's Production win in the Hutchinson 100 at Brands Hatch. Rumour had it that his Norton had a factory engine but that wasn't true. All they got from Nortons was a camshaft and a lot of good advice from Wally Wyatt before he left to go to Rickmans.

By the end of 1969 the team had seven bikes; a 750 Commando Production racer, three Commando-based short circuit racers, one Commando in a Seeley frame and the Seeley 7R and the G50. Vincent estimates that racing cost the firm £50,000 that year but that was balanced by the sales of Gus Kuhn racing bikes; a Production racer and a Formula 750 model, both based on the Commando. They also made a café racer and supplied Commando specials built to customers' requirements. There were several Gus Kuhn/Seeley kits from frame and forks up to a total rolling chassis and all this and more was illustrated in the glossy Gus Kuhn catalogue.

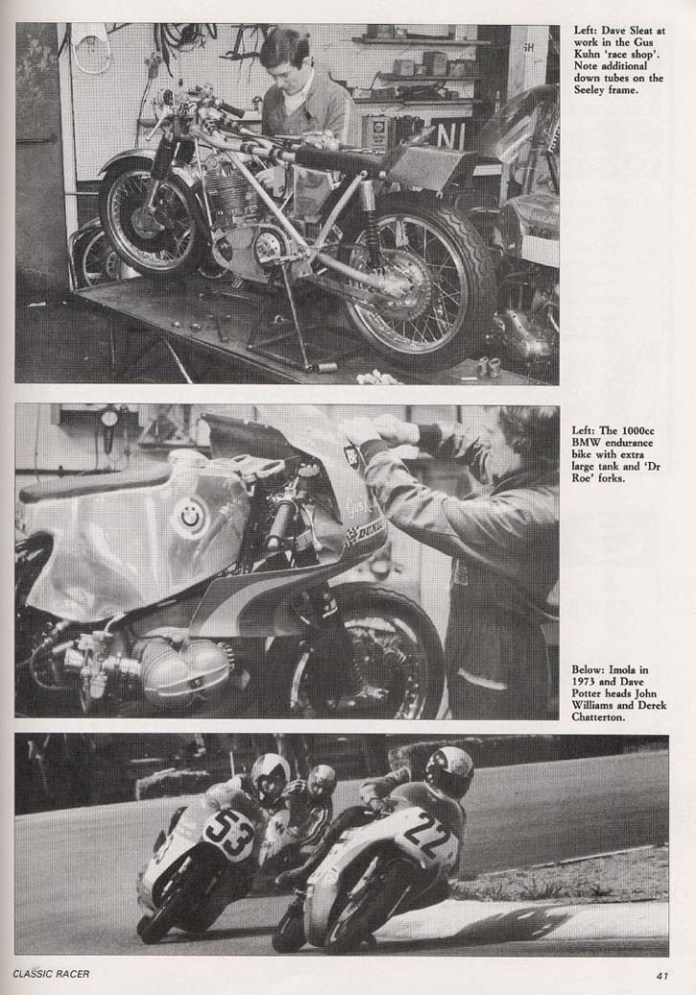

Kately and Sleat built and modified the team's Commandos in a corner of the workshop where there was barely room to swing a frame. Frank Kately left and Dave Sleat carried on with Colin Seeley preparing the Seeleys and Jim Boughen tuning the team's Commando engines.

The racers they sold had gas flowed heads and high compression pistons specially made by Omega with a compression ration of 10.25:1. The team's own engines were 11.5:1 and Jim skimmed the heads by 60 thou, which meant removing 30 thou off both ends of the aluminium push rods. A factory Norvil Triple 'S' camshaft was fitted and standard conrods had polished ends.

In their first full season the team had 23 first places and 28 seconds. Vincent had the list of race wins printed on the Gus Kuhn notepaper .. "but I had to give that up. There wasn't room for a letter!"

When he wasn't racing Mick Andrew worked as a mechanic in the Gus Kuhn workshop and lived with his wife and baby in the flat above. Vincent reckons that Mick's potential was enormous and such was his success that for 1970 Charlie Sanby and Pat Mahoney were to join him in the team. But early in the season Mick was tragically killed when, testing a Commando on the road without a helmet, he ran into a car outside the shop.

Pat Mahoney was crowned as 'King of Brands' in April and also won the 750 race at Oulton Park. Charlie Sanby won at Crystal Palace, Brands and Thruxton but crashed at Brands and wasn't fit for the TT. He won a few more races for the team later but finished the season with another crash at Lydden.

Sanby was the one-man Gus Kuhn team in 1971 and demolished Hailwood's long-standing Norton lap record (albeit on a single cylinder 500) and might well have won the Formula 750 TT race but for a broken battery lead. He won at Thruxton on a Gus Kuhn road bike and several times bettered Peter Williams on his works machine. "Vincent Davey lapped that up," says Charlie, "but it upset Dennis Poore". Years later Vincent bought two of the John Player Norton works machines and thought them over-engineered. The Gus Kuhn bikes were better in a lot of ways, he decided.

Despite its achievements, subsequent publicity and Norton sales success, the Gus Kuhn team got very little factory help until an irritated Vincent called at the Andover headquarters. They then received a measure of support - but were sent only standard parts. The Gus Kuhn racing engines were assembled from ordinary Commandos that Vincent bought complete from Norton. What was left was sold as spares. In fact, it turned out cheaper to buy spares that way ...

The Davey family were all involved in motorcycling and racing. Vincent rode as often as he could and still rides a BMW in his retirement. Daughter Valerie joined the firm in 1968 to handle team organisation and operate a stop watch at endurance races and Vincent Junior showed talent as a rider but retired gracefully after a crash at Snetterton.

Long distance races were a Gus Kuhn speciality and an outing for the whole family - especially Barcelona. Vincent entered Barry Sheene and Pat Mahoney in the 1970 24-hour race while Ron Wittich partnered Tom Dickie. The idea was for Pat and Barry to set a cracking pace to break the opposition while their team mates plodded on to finish and hopefully win. As it happened the 'tortoises' broke down and Pat and Barry were going strong until gearchange problems near the end culminated in the back of the gearbox falling of as Pat came into the pits.

Dave Sleat remembers the endurances as being very educational. He used to wander round the paddock noting all the clever mods that other teams had made. "You can learn a lot like that," he says. "Especially by looking at the bike that won."

The weak points of the Kuhn Commandos were the gearbox and exhaust. The clutch was very heavy and their last endurance Norton had the lighter Atlas clutch which had a shock absorber. It also had a roller bearing on the drive side of the layshaft, while a single chain replaced the standard Triplex. Dave spent a lot of time hand stoning all the gears so that they meshed correctly.

Broken exhaust pipes were the most common reason for the team's non-finishes in Barcelona. The Metalistic bushes for the engine and the swinging arm were set up tight, but the pipes were rigidly attached and used to break. As a cure they used a length of flexible exhaust pipe and did away with the clamps. The pipes were pushed into the megaphones by several inches and the whole ensemble held on by spring clips.

Dave used to try out all these mods on the hack Commando he used for transport but one he couldn't test was the addition of a pair of slender downtubes to the Seeley frame, welded to the engine plates and clamped to the top frame rails behind the steering head. Vibration had caused cracking of the chaincase and the crankcase but the extra tubing cured all that.

Dave Potter was the Gus Kuhn 'number one' for 1972 with assistance from American Don Emde in the Transatlantic series and the Imola 200. Dave and Graham Sharp were eighth at Barcelona where the bike consumed one set of siamese exhausted pipes, three batteries, a rear chain, a set of front disc pads, a front brake lever, one clutch cable, and a spoke in the back wheel.

The idea at Barcelona was to take it steadily and keep out of trouble but most of Potter's racing was over a few laps. Practice at Montjuich Park followed by 562 racing laps 'buggered him', he confessed, for the remainder of the season. Even so he won the 'Hutch' at Brands in August. The team had 67 rides in 36 events with 17 first places - all of which were Dave's.

In 1973 the team started racing BMWs, the works supplying bikes for the Barcelona 24 Hour race (von der Marwitz, BMWs aristo designer, delivering the bike himself), the Imola 12 Hour and the Bol d'Or at Le Mans.

"They were virtually production bikes," remembers Vincent, "with Motorsport camshafts, close ratio gearboxes and aerodynamic fairings. The trouble was they had the wrong sort of aerodynamics. They tended to take off."

Despite the bike's shortcomings Dave and Gary Green finished sixth at Barcelona with a 750. "Dave Sleat got bored," says Vincent. "He didn't have enough to do. That never happened when we raced Commandos!" They had a works 900 for the Imola race but a camshaft broke. September's Bol d'Or was run in pouring rain and Graham Sharp, suffering from shingles, was very slow. Potter tried a bit too hard at night and dropped the 900 on a pool of water. The BMW burned out (the only bike the team wrote off) but Helmut Dahne won the race for BMW on another works machine.

Team Gus Kuhn reverted to Nortons in 1974 but the factory was in trouble. Demand for the Commando had seriously declined and the price rose by £60. By now the Gus Kuhn shop were selling BMWs and MV Agusta and Potter, keen for a faster bike, asked Vincent for a Yamaha. This was not forthcoming. Vincent had decided to become an exclusively BMW dealer and had no intention of promoting bikes he didn't sell.

The team machines were BMW flat twins in 1975 with some degree of sponsorship from Penthouse magazine. They had two R90/S 900s and for endurance races Dave Sleat bored out a 900 to make 1000cc.

Old fashioned in many ways the Gus Kuhn BMWs went extremely well. "The front end of the rocker boxes used to hit the ground," says Dave Sleat, "so we raised the engines; drilling holes to take the engine bolts through the lower frame rails. After I'd done that the riders used to scrape the back end of the rocker boxes!"

The endurance racer was a handsome beast with a special large alloy tank and extra frame tubes bolted on. One inch in diameter they ran upwards from the pivot of the swinging arm to the gusset plates beneath the steering head.

Dave spent hours hand-stoning all the gears and engines were given gas flowed heads, Omega pistons and 11:1 compression ratio.

Ray Knight took a fourth and sixth place at Snetterton followed by a second for Martin Sharpe at Brands Hatch on the Production bike. John Cowie scored two seconds and two thirds at Snetterton and then in mid-May Gary Green and Potter were second in the 1,000km at Le Mans.

Seventh overall in the Production TT went to Martin Sharpe at 99.9 mph and the team won their class at the Barcelona 24 hour race where Gary Green and Potter finished fifth overall. Darrell Pendlebury and Tom Dickie were second in the class and eighth overall.

The remainder of the season was a complete let-down .. They didn't finish another race.

Things picked up again next year (1976), but without the perfumed presence of the 'Penthouse Pets'. Chris McGahan had a second, third and fourth at Snetterton; Martin Sharpe had a second and first at Brands in Production races; and Chris and Martin, on the 1000cc bike, had a second place at Zandvoort in a 600km race.

After a short lived experiment with leading link front forks, 1977 wasn't a good season. Riders Bernie Toleman and John Cowie did their best but the BMWs were outdated and soon the sober German twins made room for Yamahas and Suzukis in the Gus Kuhn showrooms. Dave Sleat began to build a TT Formula One racer with a Suzuki 750cc four in a Sprayson frame soon to be replaced by a 1000cc engine. Barry Ditchburn tried the bike at Brands and was impressed. (Click here to read more)

The bike finished sixth in the Formula One TT, piloted by Charlie Mortimer but by and large the golden days were over for the Gus Kuhn team.

The winter months were spent developing a bike for the Coupe d'Endurance races in 1978 and Andy Goldsmith and Stewart Hodgson campaigned the bike in all the big events. But Honda fours and Kawasakis were out in works supported strength and Vincent Davey realised that the time had come to quit. So ended ten remarkably successful years.

|