Alan Cathcart charts the success of Gus Kuhn Norton team

from Classic Bike Guide, October 1996

Winning a race is always a big thrill; winning a championship run over several races is deeply satisfying; but winning races and a major title by defeating the factory team from the company who built your motorcycle - especially if they've gone out of their way NOT to help you do so - must be the ultimate dream of any privateer.

One of the handful of privateer equipes who pulled off this feat was the London-based Gus Kuhn Norton team, whose riders Dave Potter, Charlie Sanby, and before them Mick Andrew, had several times defeated the works Nortons at both national and international level in production and F750 events in the 1969-1974 period. This was the heyday of big-bike 4-stroke racing in Britain, and the swansong of the Norton marque as a force to be reckoned with on the racing scene, until their triumphant return to the winners' circle with the Rotary racer! Yet thanks, no doubt, to their high-profile John Player sponsorship, as well as the advanced nature of their various chassis designs, it was the works Norton team that grabbed the headlines, whereas quite frequently, it was the Gus Kuhn riders who actually led them home.

In 1972, for example, Potter won 17 British nationals and was crowned British 750 champion on Gus Kuhn Nortons, while the following year he won one of the Brands Hatch rounds of the UK vs USA Transatlantic Trophy Match Race series, and finished 11th overall in the Imola 200 on the same machinery, on each occasion beating the JPN team to do so. Back in '72, Potter and Graham Sharp had the satisfaction of getting a Kuhn Norton home in 8th place in the gruelling Barcelona 24 Hours race after the works bike of Williams/Croxford dropped out, to be the first to coax a fast but fragile Commando to the finish of the Spanish marathon. And in race after race in the 1969/70 period, Kuhn Commandos ridden by Mick Andrew, Charlie Sanby, Dave Croxford (later to become a JPN team member, of course) and Pat Mahoney swept the board in British PR racing, firmly registering the name of the S.W. London dealers as synonymous with fast and reliable Norton roadster-based twins.

|

A certain Barry Sheene even raced a Kuhn Norton once or twice, leading the 1970 Barcelona event after 15 hours before the gearbox broke, but finishing third in the Scarborough Gold Cup the same year on a similar machine.

Unsurprisingly, their enthusiasm fuelled by this record of success on the track, the café crowd of the early '70s queued up to buy Gus Kuhn goodies for their road Nortons - thus justifying the whole exercise in the mind of Kuhn boss Vincent Davey.

"We went racing to enjoy ourselves, to put a bit back into the sport, and to get publicity but above all as a morale-booster for our staff," says Davey. "The racing effort engendered a terrific amount of team spirit in the firm, which meant that we not only had our pick of the best people going, we kept them longer too, and this benefited the customer - which of course was good for business. Mick Andrew and Dave Potter both started out working for us as mechanics before they began racing our bikes, and that meant our efforts were directed towards chaps who were one of the family. It was a happy team."

Gus Kuhn started racing at the end of '68 when Davey found himself with some spare cash thanks to a compulsory purchase order by the local council to build an old peoples' home next to the Kuhn workshop! Originally, the team contested the 350 and 500cc classes with Seeley machinery and the 750 PR class with the Nortons they were selling, but as big bike racing became more popular, he cut out the smaller classes and concentrated on the big twins. Kuhn were one of the earliest entrants in F750 racing when it was exported to Europe from the USA, furnishing Daytona winner Don Emde with a pair of Kuhn Nortons for the 1972 Transatlantic series even though their own rider, Dave Potter, wasn't selected for the British team. By then, the team had developed a very purposeful F750 racer, using Mark 3 Seeley frames with several of their own special fittings and with Commando-based engines tuned by former AMC race shop fitter Jim Boughen. "We never got any help from Norton apart from some standard parts free of charge in 1972/73" recalls Davey. "I think we were regarded as even more of a pain in the neck than the BSA/Triumph team because, especially after the John Player sponsorship came along, the Norton boys were under even greater pressure not to get beaten by another Norton team! I remember soon after the JPN team was set up, we beat them rather badly at a Crystal Palace national in front of Dennis Poore (the Norton boss) and the tobacco people. Poor Frank Perris (the JPN team manager) got told off in public by Poore before he drove off in a huff. That sort of thing didn't endear us to anyone in the Norton race shop!"

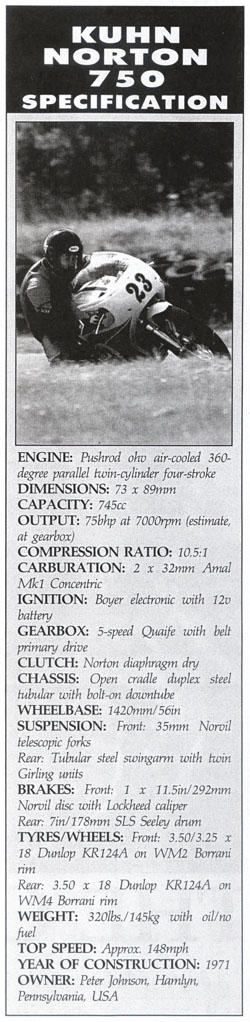

Several different Seeley-framed bikes were used over the years by the Kuhn team, being disposed of gradually as new ones replaced them, until by the last full season, 1973, two bikes remained, both painted the distinctive Kuhn colours of green with a white stripe, and raced by Dave Potter - later of course to make his mark riding TZ750 Yamahas for Ted Broad before his untimely death in 1981 at Oulton Park. Both these bikes appear to have survived intact, one in Northern Ireland and the other, after being sold by Kuhn's to Scotland and raced there with some success for a number of years by Jock Findlay, now owned by US Vintage and BoTT champion Pete Johnson.

Pete bought it some years ago, intending to keep the bike in Britain for use on his frequent business trips to Europe, but in view of his increased commitments to US competition, he's only raced it over here a handful of times. "Take it to Mallory for the day and blow the cobwebs out for me," he asked me when he phoned up one day. Happy to oblige, Peter...

Like the other Mark 3 Seeley frames (the ones with no front downtube) employed by the Kuhn team over the years, chassis No MK3CS149N was fitted by them with a bolt-on ladder-type subframe connecting the front engine mount to the headstock to provide added stiffness and to support the rigidly- mounted engine better. During its in Scotland, this was removed and the engine mounted flexibly using Isolastic mounts, presumably to reduce vibration. When Richard Peckett of P&M Motorcycles, to whom Pete entrusted the task of rebuilding the bike, stripped it out, the first thing he did was to replace the Isolastic rubbers with solid blocks to mount the engine rigidly again, to stop it shaking about all over the place when running.

However, instead of the ladder-type subframe, which could only be bolted in place when the engine was cold and not adjusted subsequently to take heat expansion into account, he fitted a single vertical strut with spherical bearings at each end that can be adjusted to ensure correct location when the engine is hot. Nice - if non-original.

The engine was rebuilt by Norton specialist Mick Hemmings, who on stripping it found that it was fitted with one of the works-type 'AMA' heads on which the big-valve conversion he currently markets for Norton twins is based. This has a re-angled, larger diameter 40.5mm inlet valve (38mm standard) on each cylinder, but with original size 33mm exhausts, with fully sphered combustion chambers; the exhaust valves fitted were nimonic to prevent breakages, and Mick also installed Carrillo rods instead of the standard alloy ones which were fitted to the bike, which Jim Boughen used to polish longitudinally.

"We used standard valve springs and inlet valves when I did the engines," recalled Boughen. "The big valves affected traction on short circuits and only showed up well on fast circuits like the Isle of Man, but I'd stopped doing Kuhn's engines by '73 and they probably fitted the big valve head for Imola, which was a very fast track in those days".

Hemmings fitted a new set of Powermax pistons, skimmed the head 60 thou to obtain 10.5:1 compression, and flexibly mounted the twin 32mm Amal Mk1 Concentric carbs. Instead of the points fitted to the bike, he installed a Boyer electronic ignition running off the 12v battery positioned under the vinyl flap in the distinctive Kuhn seat: Richard Peckett has had new moulds made for all the bodywork, by the way, and can supply any part seen on the bike to order, including the large-capacity TT fuel tank. A 4S camshaft, hottest of the Norvil range, is fitted now as then. "We ran a 4S cam, points ignition and pulled the timing back to 28 degrees," said Jim Boughen. "Lucas Rita electronic ignition was just coming in then but it was pretty crude and not very dependable: we hacked a lump off the timing cover on a couple of engines to fit it, but went back to points as there didn't seem any advantage." Pete Johnson's bike has just such a part of its timing cover removed...

Mick Hemmings sent the Kuhn Norton crank to car restoration specialists Bassett Down Engineering to be dynamically rebalanced, fitted his own belt-drive conversion for the 5-speed Quaife close-ratio gearbox to replace the original triplex primary chain, and retained the standard Norton diaphragm clutch, now of course running dry.

"The reason it took us so long to finish a 24 hour race was because Vincent Davey would insist on running that heavy old Norton clutch," insisted Jim Boughen. "I wanted to fit a nice light AMC racing unit which would also have reduced a bit of weight and complication, but he wouldn't have it, so of course the transmission usually packed up after eight or twelve hours".

No such problems in UK short circuit racing where the Kuhn bike spent most of its life and the belt drive conversion offers much greater convenience as well as durability.

Slotted back into the Seeley frame, freshly re-built by P&M, and with the bodywork re-painted in what I might term neo-JPN livery rather than the original Kuhn colours, the engine yielded some enjoyable rides on the bike, if not a lot of success compared to Pete's win over Dave Roper in the 1987 US F750 Vintage title, riding his P&M-built Triumph-3. My trip to Mallory was as much to see if the bike could be sorted out a little more, as much as to sample it for myself. But having recently ridden the Kuhn Norton's great rival during the 1972 season, the pannier-tank JPN now owned by Joaquin Folch, it was a great chance to compare the two great adversaries for the title of King Norton.

Chassis-wise, there's no contest: the Seeley-framed Kuhn wins hands down. Like the JPN, the riding position is very low and tight, different than Seeley G50s I've ridden and almost certainly due to the big tank and shapely, curved seat: you sit in the bike, not on it. Even though 18 inch wheels are fitted front and rear, and the twin rear Girling units are the long 12.75 inch ones, you feel as if the rear end is squatting lower than the front, again like the JPN I rode with a 19 inch front wheel. But whereas that bike steered in a slow, lazy fashion that was steady, but far from nimble, the Kuhn has finely-balanced, neutral steering that makes it ideal for the hurly-burly of short-circuit scratching.

Over Mallory's bumps the Norvil front end and sticky KR124A Dunlop coped well, and exiting Gerards the power could be fed in gradually without the front end under-steering as it does on so many bikes there. The rear end hopped and skipped a bit, almost certainly due to too stiff springing for my weight, but after a few laps I found myself at home, enjoying the chassis that has to be the epitome of the black art of frame design as honed to perfection by Colin Seeley and his men in the 1960s.

|

Interestingly, this frame seemed to 'talk' to the rider more than Seeley frames fitted with G50 engines, which are almost too stiff and can sometimes step out on you without any prior warning. Maybe the extra weight of the twin-cylinder engine made the Kuhn's frame more responsive, but it's a bike that inspires confidence. The single front disc provides quite adequate stopping power, even at Mallory's walking pace hairpin, especially allied with the notable engine braking available from the lusty motor. But then flip-flopping it through the ludicrous chicane belied the fact that this was a 750, especially by the standards of one of today's four-cylinder Superbikes: the Norton felt more like a 250 GP bike in comparison.

But the engine's a different matter. Strong, yes; fast, certainly; rider-friendly, NO! I've ridden several racing Norton twins over the years, including some very hot ones such as Merv Brookes' Fair Spares title-winner a few years back, but I can honestly say I never encountered one that vibrated as badly as this. Now I can understand why the engine was rubber-mounted, presumably to make it at least halfway rideable, even if a lot of the power is thus thrown away down the frame. There's not a lot of poke below 4000 rpm, but then it comes on song very strongly and pulls like a tractor up to peak revs of 7200 rpm. Or rather, it would do, if you could persuade yourself to hold the throttle open long enough for the rev-counter needle to get that high - that's before it broke off altogether due to vibration, as it did after a dozen laps! - but the immense vibration that sets in just over 5000 revs discourages such notions. You feel it everywhere: in your hands, your feet, through the seat of the pants - it's an all-pervasive vibro-massage that frankly makes riding the bike at competitive speeds difficult, if not dangerous. Yet a tantalising glimpse of the Promised Land is afforded by the way the Norton picks up its skirts and fairly rockets down the straight when you get it wound up: just that with everything shaking around, including your eyeballs, it makes it kinda hard to know when to slow down for the next corner...

It also makes changing gear on the close-ratio 5-speed Quaife gearbox less easy to do smoothly, though I suspect the reason that the top two changes especially are less than ideal is because of the crossover linkage to permit the one down, left foot change that, being a Yank, Mr. Johnson prefers.

Obviously something's wrong, given that the carburetion isn't too rich and all quick Norton twin-cylinder racers have rigidly-mounted engines: more to the point, that's how Kuhn built them back then. Having lived with a similar kind of experience on my G50 Matchless while Ron Lewis was experimenting with various balance factors, I don't think there's much doubt that that's where the problem lies: the crank's been balanced incorrectly. Jim Boughen again: "We used to lighten the flywheels by using different centres, but it meant we had to use an unusual balance factor for Norton twins of 78%, and a very special material called 'heavy metal' to balance the cranks, which we got from the nuclear research establishment at Harlow. Whatever vibration we ever got could always be cured by rebalancing the crank, and the engines were so smooth that Emde said it was almost like riding a 2-stroke when he raced one of our bikes. We'd use 7200-7300 rpm normally without any problems with things falling off and with the 4S cam there is quite a bit more power at the top end, so you want to rev them a bit."

Well, Pete - there's your problem, I reckon: have a go at rebalancing the crank and I'm sure you'll have a very fast, as well as very historic motorcycle. And one that might give the BSA/Triumph triples that rule F750 Historic racing today a wake-up call! |